The Mito Koumon fireworks display: A celebration of community

Expectations in the community seemed very high for the fireworks display this year due to the cancellation of the fireworks each year for the last three years. I set out from my house with a picnic lunch en route to the venue of the fireworks display at Lake Senba. The closer I got, the greater the number of people I saw, all headed in the same direction. The atmosphere had the feeling of anticipation and excitement akin to a live performance of one’s favorite music group. Community events draw people together and help forge bonds of goodwill. These events also shape the identity of the community. Mito was throwing a party that night, and many, many people wanted to join in the fun.

Anticipation of the event grows in accordance to one’s preparation for the event, and my preparation had started before sunrise that day. I had risen early to cycle to Lake Senba for the purpose of selecting a spot lakeside, opposite where the fireworks would go up. I reserved my spot by staking a tarp into the ground. I was by no means the first. Many people already had claimed their spot. The area looked like a quilt of various colored tarps, fastened willy-nilly to the ground.

The timing of the festival was different this year. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the fireworks display had been held each year in early August. Now in October, the flurry of food vendors lining the walkways suggested summer, but now there was a definite autumn tint in the air. There were fewer summer kimono, yukata, among the festival attendees. And there was less daylight. It was already growing dark as I threaded among the crowd to reach the spot I had claimed that morning. Sitting on the ground lakeside, I appreciated the lights of the festival from across the lake, lights that were reflected in the still water of Lake Senba. The reflection of the festival lights on the water had a nostalgic ambience, as though festivals from years past had broken the chains of time in order to be part of this year’s festival. Certainly, many people have lost and suffered due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. Perhaps the nostalgic glimmer on the water reaches back to a time before Covid-19 when we imagine that we had fewer worries and could take fewer precautions. It seemed that tonight’s fireworks display in part was to help people set aside their worries so that they simply could enjoy the beauty of the fireworks.

The preparations for the display helped people join in the fun. The entire lake was wired for sound, and some of the fireworks were set to music. Thirty minutes before the display, a single, four-report signaling firework, the kind which is used to announce a school sports festival, informed festival goers that the time was drawing near for the fireworks to begin. People settled in to their selected spot or hastily selected a spot to view the fireworks. Judging from the number of people who gathered around my tarp, I had selected a desirable location from which to view the fireworks.

And then it started. Let there be no doubt: A fireworks display is a work of art. As with a musical symphony, there are crescendos and a flow to the performance. Timing has been considered to maximize the effect upon the astounded viewers. Perhaps the weather is the only thing beyond the control of the modern pyro-technician. Each firework is a highly refined work of art that varies in color, shape and evolution. Such is the high level of control in modern fireworks that Mito-chan, the mascot of the city of Mito, also was represented in a firework. Certainly, some fireworks suggest their predecessors of years ago, but the modern version no doubt is bigger, brighter, and more astounding than its forebears. At one point the fireworks display was effectively coordinated with music created by a local composer. It is a challenge to the viewer of a contemporary fireworks display to maintain one’s unwavering focus upon the canvas of the sky in order to appreciate in each moment the wonder that constantly unfolds in the sky above. Without such a focus of mind, one quickly becomes overwhelmed by the sensory overload of the display. The Mito fireworks display was powerful, glorious and well-nigh overwhelming. A short break in the middle of the display enabled people to return to Earth, catch their breath, and prepare themselves for the rest of the display. The display after the break was a fabulous denouement which challenged the viewer to an ever-higher peak of ecstasy. If the ovation afterwards was less than it should have been, I think it was because people simply were too moved by the display to clap their hands once the display was over. They had poured their energy into the glory of the fireworks and had nothing to give after it was over.

In the aftermath of experiencing this stupendous work of art, people began their journey home in an orderly manner. They seemed to be slowly returning to their daily lives, from which, for a brief span of time, the fireworks display had released them. Great works of art place the human experience in perspective. In viewing the fireworks, I deepened my appreciation of the efforts that we make as members of a community to work towards collective goals. The fireworks display is one of the high points of living in Mito, and each person who helps bring it to pass deserves to be commended. The display is a celebration of community, and I feel very fortunate to be able to join in the fun. Congratulations, Mito!

Excellence in the arts

The modern arts center which is Art Tower Mito (ATM) points to the priority given to art in the life of the community. The arts complex features a concert hall, a theater for dramatic performances, an exhibition gallery, a pipe organ, a gift shop, a restaurant, and an original art tower. My initial and abiding impression of the design of ATM is geometrical: It is as though an architect used the forms of the square, the circle and the triangle to design the entire complex. An architect in New Zealand stated that he studied the design of ATM at university, so the arts center clearly is being acknowledged internationally. The open space in front of the art tower is used for outdoor installations, concerts, and various public gatherings such as flea markets. The fountain which features the dramatic suspension of a multi-ton rock, transforms into a wading pool for children during the summer.

A problem in many countries is the prohibitive cost of artistic performances. ATM features a number of free performances throughout the year. Visiting organists perform for free on the pipe organ a few times a month. The promenade concert series at ATM also features soloists, duets, trios and small ensembles performing for free on a variety of instruments. I regularly attend such musical events and remain grateful to ATM staff for scheduling these performances.

The open space in front of the art tower becomes the venue for music performances throughout the year. During the Mito Komon festival, a variety of rock and jazz groups take the stage. In December a large choir performs Beethoven’s ninth symphony, despite the cold (though I understand that on especially cold or snowy days, the performance is moved to the concert hall indoors).

I try to stay informed of what is happening at the ATM. Knowing what’s happening at ATM helps keep me in touch with the pulse of the community. The ATM staff is well-informed and ever gracious. It’s always a pleasure to take in the performances at ATM which I view as part of a well-lived life. Congratulations to the people of Mito for having created ATM and for continuing to support it!

Harvesting rice, the old-fashioned way

It was an early fall morning when I set out by bicycle to help my friend Hiroshi harvest rice. It’s easy to bicycle in Mito; the terrain is relatively flat, the distances to most destinations usually are not far, and drivers are for the most part respectful of cyclists. The beautiful color of the autumn leaves added to the enjoyment of the ride.

I skirted the Mito campus of Ibaraki University and started down a hill into the flood plain of the Naka river. Old-timers had told me stories of when the Naka river flooded in times past. One man had to be rescued by boat from his window on the second story of his home before the levee was built. Now the paved path atop the levee provides an inviting path for cyclists, walkers and joggers. Even with the levee, the sheer accumulation of water after a typhoon a couple years ago flooded the low-lying fields around the Naka river. There simply was no place for the water to go. Harvesting rice from one of these flooded fields was my goal for the day as I crossed the old iron girder bridge over the Naka river.

Rice farmer Hiroshi believes in harvesting rice the old-fashioned way: We were to construct a rack and hang bundles of rice upside down to dry. Those in the know tell me that drying rice in this manner increases its flavor because any remaining nutrients flow to the kernels in the upside-down plants. The vertical poles of the racks were metal. The horizontal poles on which we actually would hang the rice would be bamboo. We would use rope made of rice fiber to attach the bamboo to the metal pipes. In this sense, Hiroshi was making some concessions to modernity in an approach that for the most part was traditional.

Hiroshi stated that almost no rice farmers harvest rice in this manner any longer, and I soon understand why. It is a very labor intensive process, requiring the effort of a group of people (the more, the better). Among the helpers today would be four assistant-language teachers from the United States as well as members of Hiroshi’s family. This group approach to harvesting rice reflects the history of rice cultivation in all of Japan. The entire process of leveling the fields, bringing adequate amounts of water to the field during and after planting, then harvesting were traditionally very labor intensive processes, especially given the rudimentary technology available in the past. Soon after coming to Ibaraki, I remember asking one farmer how old his rice field was. When had the area been leveled with access to water? He didn’t have a clue. This points to the age-old nature of agricultural developments in a country occupied for many centuries. Important steps such as when the paddies were constructed are now consigned to the mists of the distant past.

At one point we ran out of horizontal bamboo poles on which to hang the rice. Hiroshi’s solution was simply to transport his helpers to the nearest bamboo grove to cut some bamboo. How handy! As the tall, lean bamboo fell one by one, we stacked them atop the pickup truck. We hauled the bamboo to an area near the metal poles and then started to hack off the bamboo branches. Bamboo is a beautiful plant. I can see why it is featured in numerous scrolls and other works of art throughout Asia. It is light and strong and grows remarkably fast. I think of it as a building material of the future.

In many countries of the world, including Japan, many of us eat rice every day. Without getting involved in rice planting and harvesting, however, we have little understanding of what it takes to produce rice. This is the motivation behind those of us who participated in the harvest: To get a hands-on appreciation of what it takes to produce this all-important staple grain. Our process was simple: We cut the rice with hand scythes close to the ground, tied it into bundles about 8 centimeters in diameter, then divided the bunch down the middle so that it would hang securely on the bamboo rack we had constructed. We filled each rack that we had set up with beautiful rice. Looking at the wall of rice, I could see why tatami mats would catch on and remain a part of Japanese homes. It’s an attractive and versatile fiber. And especially in the Japan of yore, waste-not-want-not would have been the prevailing ethic.

We took a break around noon for a meal of curry rice. Manual labor produces an appetite: We ate all that there was, and everyone cleaned their plates. We admired the dragon flies darting to and fro. I started to hum the traditional song about dragonflies, Akatonbo. After a few more hours, we admired our labor, took numerous photos of the racks full of hanging rice, and then headed for home. I look forward to eating the first rice of the harvest once it is dried. But some things take time, the old-fashioned way. When I ladle the first harvest of steamed rice onto my plate, I’m sure that I will conclude that the effort and the wait were worth it.

The past is present

What many foreign visitors want to understand in going to a new place is how the local people survived and developed over time. Education is an important component of historical change, and Kodokan emerges as an important place in the history of changing Japan. Kodokan opened in 1841 as a school for feudal warriors and their children. Topics of instruction included Confucianism, history, astronomy, mathematics, music, and various martial arts such as fencing, spear wielding, military strategy, and horsemanship. The area of the school preserved today is about one-third of the total area of the school when it was established. These extensive grounds point to the priority given to education at the time, despite an extended famine in Mito from 1833-37.

I feel very fortunate to have visited Kodokan when I did. Visitors on the day that I entered were allowed to enter Kodokan through the gate reserved for the feudal lord. As one ascended the stone steps leading to the gate, Kodokan and the plum and cherry blossoms of the park came into view. No doubt many students of Kodokan revered the place not just as a center of learning, but of beauty as well.

The beauty of the building and the adornments convey important lessons. The meaning of the calligraphic scrolls emphasize that a broad education leads to a balanced life. I could grasp such meanings due to the detailed English signage on the grounds of Kodokan. As a foreign visitor to Kodokan, I smiled in learning that Nariaki Tokugawa, the ninth feudal lord of the Mito clan and the one who established both Kodokan and Kairakuen park, was against letting foreigners enter Japan (so much for that idea).

The spacious grounds of Kodokan are delightful. The landscaping is well-done and low-key, fully in keeping with the edification of the viewer. I could imagine students walking among the flowering plum trees, reflecting upon their recent learning. A breeze caused some petals of a plum blossom to flutter to the ground. The esthetic of the calligraphic scrolls and the gardens seemed to complement each other.

I feel that an important part of Japan’s history is on display at Kodokan: Education as a contributing factor in the unification of Japan, resulting in the Meiji emperor as the leader of the growing nation. It’s ironic that Nariaki Tokugawa, in creating the school and encouraging people to think for themselves, may have contributed to a stream that culminated in the end of the Tokugawa era. Be careful what you wish for, I guess.

Opposite Kodokan is the new Otemon gate. It is a splendid structure of massive wooden beams that harkens back to the feudal era. I’ve heard that as the wood ages, it will grow in character and become even more attractive. A short stroll beyond the gate is the Ninomaru Exhibition Room. It informs visitors of the historical character of the area. I also learned of the connection of Kodokan to other schools in Edo era Japan.

Kashima shrine is on the northern part of the grounds of Kodokan. An exhibit at the shrine featured delightfully designed, detailed lamps made of gourds. One would cut a gourd on the bottom, hollow it out, then drill holes on the surface of the gourd to create various patterns. When one puts a light bulb inside the gourd, the light shines through the holes, revealing the design. Colored glass and acrylic enhanced the effect.

The delights of Kairakuen Park and the plum festival

Impression:

Renowned as one of Japan’s three most celebrated parks, Kairakuen park in Mito is enjoyable to visit year-round. It combines features of a modern park and a traditional Japanese garden, so there is plenty to see throughout the year. The park is so expansive that one can find what one is looking for and still have room left over for many, pleasant discoveries.

I went in the early morning during the plum festival, a time which particularly draws in the crowds. The park opens at 6 a.m. during the festival, and at that hour I leisurely walked on the walkways of Kairakuen park and could appreciate the spaciousness of the park. The power spot of the towering cedars is impressive. The bamboo grove is regal and austere in its restrained verticality. The flowering plum trees are quite delightful, almost extravagant in the profusion of the blossoms. Plum fragrance fills the air. It is a fitting place for a romantic stroll with a partner, and even in the early morning I saw many couples leisurely walking through the park, enjoying both the beautiful scenery and each other. A botanist might point to the many species of plum trees featured in the park, but such distinctions probably are lost on most visitors.

An atmosphere of old Japan remains within the boundaries of Kairakuen park. Kobuntei is an exquisite structure that transports the visitor to the refined life of the nobility in Edo era Japan. I understand that the plum trees and the bamboo point to the needs of an earlier era: The plum trees could provide food, and bamboo was the raw material for making bows for the military defense of the area. Throughout the year, traditional tea ceremonies are offered on the grounds of the park and in Kobuntei. The landscaping, the fencing, and the lighting in the evening are tastefully done and complement the overall ambience of the park.

As I walked through Kairakuen park, the restrained esthetic of various places in the park struck me repeatedly. The plum blossoms are naturally beautiful in their simplicity. With each step, the alluring fragrance of the blossoms grows stronger or fainter, almost like a pair of beautiful eyes hiding behind a fan. The tall cedars are mighty guardians in their unadorned majesty.

And I learned about a traditional lucky charm in Japan: Shou-Chiku-Bai, or pine-bamboo-plum. In the winter, transitioning to spring, the pine stays green despite the cold, bamboo represents straight, supple strength, perseverance and fortitude. Plum trees patiently endure the cold of winter to bloom in the early spring with beautiful flowers. Pine, bamboo and plum trees are considered to be happy plants and symbols of good fortune and longevity. The saying, “Shou-Chiku-Bai” is an auspicious sign used in celebrations. I found it a very apt lucky charm to learn about during a visit to Kairakuen park.

A plum lunch

Sansui is a tasteful restaurant in central Mito that skillfully draws upon and contributes to the culinary heritage of the area. I enjoyed the plum lunch and noted on the menu other dishes that are part of the culinary heritage of the area, including angler fish stew. The plum festival in Kairakuen park draws throngs of people each spring to view the beautiful blossoms, and the culinary specialists at Sansui highlight that event by showing what one can do with the sour, pickled plum.

“Sour” and “pickled” are not necessarily words that Westerners associate with the word, “plum,” which is a sweet fruit in many countries. The Japanese plum is a bit smaller and can be used on the sweet side in such items as fermented plum wine and plum jam and sauce. In many parts of Japan, however, the plum is perhaps better known in its sour, fermented form, called “umeboshi”: It is placed in the middle of rice balls or served on the side as a sour, salty complement to other dishes. Umeboshi has its fans as well as detractors; it probably ranks right up with natto, or fermented soybeans (for which Mito also is well-known) as a make-or-break foodstuff. You’re either with us or you’re not, and umeboshi has a way of making you declare your allegiance one way or another. I’ve long been a fan of umeboshi, and my appreciation for it deepened as a result of my visit to Sansui.

Sansui strikes me as providing customers with the optimal combination of traditional and modern Japan. The façade of the building harkens back to an earlier era. One parts the hanging textile at the entrance to go into the restaurant. The décor is refined and restrained in a traditional manner. The intimate room for two in which I dined had an in-wall sculpture, an antique lamp and a sliding wooden door. The tableware and ceramics were traditionally stylish.

The lunch was served in courses which were small and tastefully presented in a way that appealed to both the eye and the palate. The waiter was gracious and well-mannered. In response to my questions, he clearly was well-informed as to what he was serving. The lunch started with konyaku (“devil’s tongue”) sashimi, the slices of which were soft and quickly consumed. This was served with sea bream sashimi in strips that wrapped around different fresh greens. In keeping with the theme of the lunch, the sashimi came with a sour plum sauce that clearly referred to sour, pickled umeboshi, but was well-rounded and subtle enough to be palatable even to those who generally eschew umeboshi. I subsequently enjoyed spring rolls that had a plum accent to them. I understand that the vegetables in the spring rolls come from Ibaraki. The spring rolls quickly vanished from my plate.

A fillet of sea bream featured a plum sauce blended with mayonnaise. Sea bream is associated with celebratory occasions in Japanese cuisine, which seemed appropriate as I was celebrating this sumptuous cuisine. Yuba, a byproduct of making tofu, was served with a pickled plum, and they complemented each other well. I removed the wooden lid from a traditional vessel for steaming rice and used a large, wooden spoon to ladle rice into my rice bowl. I topped the rice with fish flakes and a pickled plum topping. Hot water also was on the table if I wished to add water to my second or third bowl of rice to consume it as a thick broth. Miso soup and pickled vegetables (radish, cucumbers and carrots) rounded out the meal.

While the restaurant was quiet enough to converse easily with the waiter, the meal was punctuated with the chatter and laughter of other customers. Sansui was busy; without a reservation, I might not have been able to get a table. It clearly is a preferred destination for people who wish tasty fare that is prepared and presented well. Those in the know tell me that well-regarded rice wines also are featured on the drinks menu. I hope to sample them in the future during a return visit.

A visit to Lake Senba and the Ibaraki Prefectural Museum of Modern Art

The Ibaraki Prefectural Museum of Modern Art is on a hill above Lake Senba in Mito. The grounds of the museum feature scuptures, a reflecting pond and the preserved studio of a well-known artist, Mr. Tsune Nakamura. The museum is a large facility with generous space for permanent and temporary exhibits. It also has a concert hall on the lower level. Periodic workshops offer both children and adults an opportunity to learn a new artistic technique and to hone their creative skills.

I went to the museum on a brisk autumn morning for a jazz concert. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, advance registration for the concert was required. A pianist and a Japanese flautist on a traditional instrument called a shakuhachi teamed up for an exquisite performance of jazz standards and jazzy Japanese folk songs. The concert venue is intimate, with very attractive acoustics.

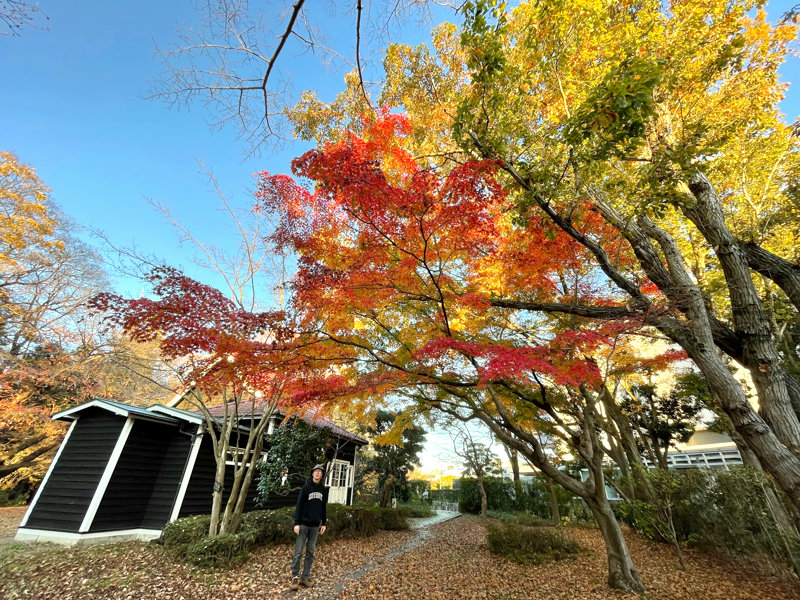

After the very enjoyable jazz concert, I explored the grounds of the museum and walked and cycled around Lake Senba. The fall color of the grounds of the Nakamura studio next to the museum was resplendent. Strolling down to the lake, I immediately saw two, large fountains in the lake which provide an ever-changing display. I could view the fountains from many points along the approximately three-kilometer path around the lake which is shared by walkers, joggers and cyclists (a shop on the west end of the lake rents bicycles). Numerous waterfowl adorn the lake and have long since lost their fear of people. The lake sometimes features large-than-life, white swans. These are rental paddleboats. Drainage from Lake Senba into the adjacent Sakura river ensures a constant level of water in Lake Senba. Benches around the lake enable visitors to admire the well-tended green space surrounding the lake and to view the urban skyline to the north. Though visiting in the autumn, I was very surprised to discover some blooming cherry trees. Lake Senba is lined with cherry trees, and the view in March and April when they are in full bloom is quite impressive. Evening viewing when the blossoms are lit up with tastefully placed spotlights also is a unique attraction of Lake Senba in the spring. The south side of Lake Senba features extensive grounds for picnics, strolls and events. When I visited, many vendors in the event space were selling both food and souvenirs. An organized run around Lake Senba is a regular part of activities during the New Year break.

Lake Senba narrows on the west end, and that’s where I found the large statue of the patron saint of Mito, Mito Koumon. Mitsukuni Tokugawa was the leader of the Mito domain in the 17th century. He assembled scholars to compose an influential history of Japan which subsequently spurred nationalism both locally and throughout Japan. A TV show drawing upon his somewhat fictionalized exploits became a popular period drama and is still watched.

Adjacent to the statue of Mito Koumon is the Kobun café. An open terrace above the café offers an expansive view of the lake and its surroundings. Couples indulge in the romantic gesture of ringing the bell on the terrace. A nearby teahouse, Koubun Chaya, features local delicacies in a traditional setting.

The modern art museum and Lake Senba always have something attractive on offer. Whether the visit is planned or spontaneous, exploring Lake Senba helps one connect with the ambience of Mito.